Earlier this year, in May, I had an opportunity to visit Rome. Here at last was an occasion to finally experience this famous city. I had been here before, on business, but always in a rush. Now I could take my time to savour the place, giving myself 4 weeks to do so.

Visiting Rome is not like visiting some other capital. This was Rome, the “Eternal City”, which some even called at one time the “Caput Mundi” – the capital of the world, no less!

Since it was founded 28 centuries ago, it started out as the capital of the Roman Kingdom, then became that of the Roman Republic, then of the Roman Empire, then (and still now) the seat of Roman Papacy, before finally becoming, in the 19th century, the capital of the Kingdom of Italy. To many of us westerners, it is the cradle of Western civilisation and Christian culture. That makes it the oldest, continuously occupied and still standing capital city of Europe.

Clearly, there is much to be learned from a place like this.

Antiquity and Ruins

When you arrive from the airport, the first thing you notice of course are the ruins, in a beautiful green and ochre setting. Gone are the sight of those Renaissance paintings, that showed them littered all over the place, overtaken by vegetation, half buried and in a state of advanced decay. Today they are all cleaned up, erect and looking forlornly. What was it, I wondered, that drove us to suddenly want to unearth all these ruins, in the early 19th century? It seems it was a combination of factors:

– The emergence of the newfound discipline of archaeology

– A number of highly educated and rich men, with much time on their hands, who became quick adepts of this new discipline, and developed a sudden passion for our past.

They had the means to fund such excavations, all over the European Mediterranean basin, and were in the grips of wanting to uncover and restore ancient ruins.

– A desire to learn more about the age of humanity, to understand how ancient civilisations lived and functioned. Maybe also a way to combine the recent Darwin and Wallace’s Natural Selection theory with human antiquity.

– It was also a way, I guess, to counter the dehumanising effects of the Industrial Revolution, maybe also to deepen our faith in the evolution of our own civilisation.

And what better place to dig things up than in Rome?

Rome today offers a very unusual and chaotic urban landscape. All these ruins all over the city, surrounded by many basilicas and churches, Renaissance buildings, contemporary stone ones, interspersed with hilly parks full of umbrella pine trees, with here and there streets lined with occasional orange trees, or tall, majestic palm trees. All this amidst the hustle and bustle of an often tightly knit network of winding, cobbled streets here, large outdoor flying stone stairs there, and so on. All this just draws you in like no other capital city that I know of. And hills all around.

As I wander amongst all these ruins and the more modern avenues, my old history lessons float back into memory. Castor and Pollux, Nero, Caligula, Cicero, Crassus and Pompey, Julius Caesar, the Rubicon (which I discovered is nowhere near Rome), Augustus, Constantine, the Capitol and its geese, the Coliseum, the Pantheon etc. There is something comforting to finally be able to amble along and associate all these past stories with a location. Which, of course, is the whole point of preserving all this in the first place, despite all the very large space they take up. It also makes me realise how much we are still so connected to our Roman past, how it continues to inform us about our roots, our present culture, the origin of our politics too (not much has changed since on that front).

Christianity and the Vatican

Rome started out as the seat of power of a pagan empire, that lasted more than 600 years. When that power started to wane, exhausted by so much brutality, violence, barbarism, licentiousness and so on, a counter mouvement started to emerge very gradually. People aspired to something more uplifting, looking for hope, redemption, love, fellowship. In came religion in the form of Christianity. It took over 3 centuries to emerge, when Emperor Constantin, as he was nearing death, suddenly and opportunistically decreed that Christianity was to become the official religion of the declining empire. From that day on, instead of pagan and Jews chasing and killing those new Christians, the chase was reversed and Christians started chasing the pagans and Jews, just as mercilessly killing anyone of those who did not convert to the new faith. Christianity was set to become, over the coming centuries the largest religious faith of humanity, with some 2.4 billion followers, or 30% of today’s world population. In reaction to a decaying empire and the sudden decree of a dying emperor !

I am told Rome today has over 900 churches within its walls (apparently nearer 1,600 if you count private chapels). Everywhere I turn in Rome, I see a church.

And because the decreeing emperor was living in Rome at the time, that is where the Vatican City was to be eventually founded. Although called a city, the Vatican is an independent country inside the boundaries of city. The only instance in the world for such a strange phenomenon.

The Vatican is not just a ‘country’ in a city, it is also the seat for the largest religion in human history. And still going strong after 17 centuries of existence.

It all started on the west bank of the Tiber River, originally a marshy area which the Romans considered dismal and ominous. An area, at the time, continuously flooded by the river, which did not stop the Christians from building their first Constantinian basilica, in 326 AD.

I visited the Vatican City twice during my stay. Regardless of your religious affiliation (I am a non-practicing catholic), this fortified micro-nation has left a lasting impression on me. Trust me, if you go there, you will feel the same way.

Probably the strongest impression you feel is that of overwhelming power. The sheer size of today’s Basilica, together with all its unbelievable luxurious adornments, is compelling, extreme, verging on the oppressive.

But then that is exactly why Julius II had St Peter’s rebuilt in 1506. He was known as the “warrior pope”, who undertook an aggressive campaign for political control by the Catholic Church over the various lands of the Italian peninsula and well beyond. That Basilica was designed to be a potent symbol of power and it unmistakably still hits the mark magnificently.

The Sistine Chapel

The same goes for the Sistine chapel, inside the Vatican, plastered with wonderfully preserved frescoes, from floor to ceiling. The Renaissance equivalent of wall-to-wall modern propaganda that would make today’s Chinese Central Committee green with envy. Not a single piece of wall has been overlooked. The ceiling of the chapel is 40 metres long and 20 meters high and was painted by Michelangelo. It is so high, I regretted not having a good pair of binoculars to really appreciate the craftsmanship.

It turns out Michelangelo had rejected the commission when it was first offered to him by Julius II. That was because he thought of himself more as a sculptor, who preferred to mould materials, then as a painter. And he knew nothing about fresco painting. But Julius II was an authoritarian man, he insisted, leaving Michelangelo with no other option than to yield.

So in the end, the sculptor learned about fresco technique and took a crash course on it in his home town of Florence. He ended up painting the whole 40-meter-long ceiling on his own, while still in his early 30s. It took him, on and off, 4 years to complete this monumental undertaking. I cannot think of any artist today who would contemplate such an enormous undertaking. I found out he did this standing up on gigantic scaffoldings rather than by reclining. I wonder what effect that must have had for his physical health.

The result, with over 300 different individuals depicted, is just beyond speech. Both for originality and sheer boldness. And I am not even referring to the radical Renaissance liturgical interpretations Michelangelo made when painting these frescoes, which he apparently more or less did of his own volition. It just takes your breath away, even without binoculars.

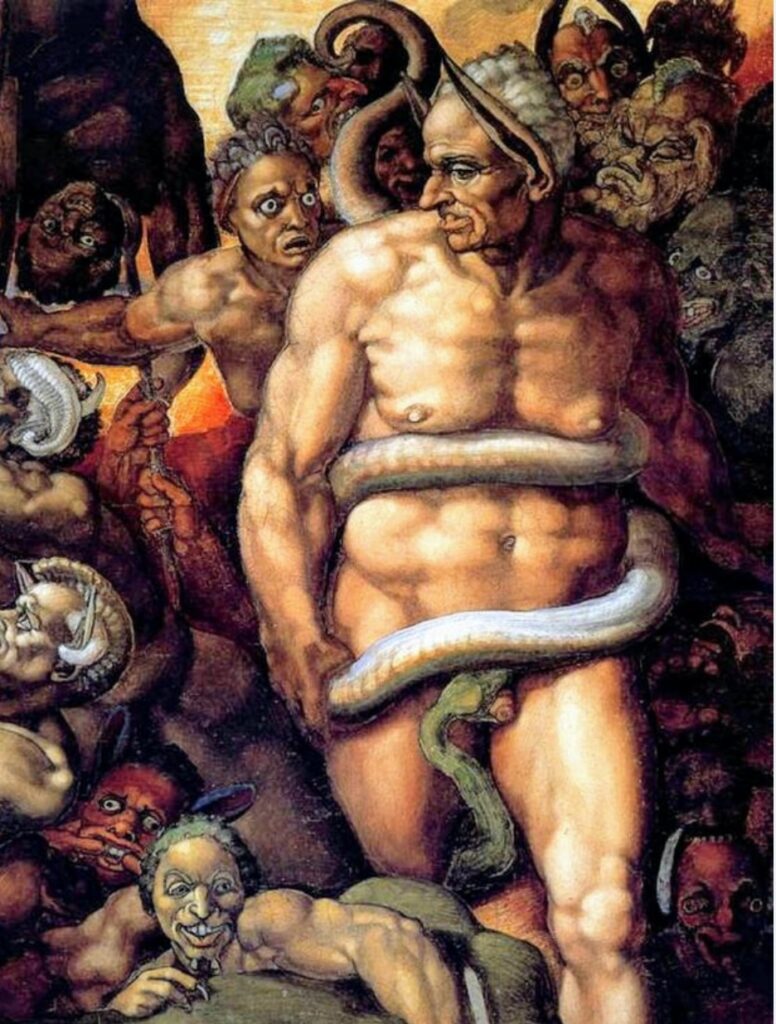

As if that was not enough, a successor pope subsequently asked Michelangelo again, some twenty-five years later, when he was in his 60s, to undertake the painting of The Last Judgement wall behind the altar. Another monumental task, as that meant painting a fresco high of 14 meters and 12 meters large. Even though I do not subscribe to the story told on that wall, I was spell bound by its unbelievable originality. I just cannot find the words for it except to say it was brazen as well as monumental.

The ceiling took over 4 years to complete. The 300 different individuals it depicts are mostly men, showing off their muscular nudity. This proved very controversial at the time. Michelangelo probably came to expect it, though it did not prevent him from painting them.

As to the back wall for the Last Judgement, there are a couple of interesting stories about it.

One was about the Pope’s master of ceremonies, a certain Biaggio da Cesena who is reported as having said: “It was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but (one) for public baths and taverns”. Michelangelo immediately worked Cesena’s face from memory and incorporated him into the fresco. He represented him as Minos, the judge of the underworld, with donkey ears (showing foolishness), while covering his private parts with a coiled snake biting his privates. When Cesena went to complain to the Pope, the pontiff joked that because his jurisdiction only extended to Heaven, not to Hell, the portrait would have to remain.

Another interesting story is that, after Michelangelo’s death, the Council of Trent formally condemned the portrayal of nudity in religious art. So, a succeeding pope commandeered a pupil of the deceased painter to paint over the offensive parts, with draperies and breeches. That quickly earned the painter the nickname of “Il Braghettone” (the breeches maker). Italian wit.

I also visited the museums of the Vatican, which house hundreds of thousands of untold treasures: sculptures, paintings, and objects of all sorts, amassed from the four corners of the world.

Out of all these, one artefact really struck me. Namely Nero’s bathtub. In dark red porphyry, and measuring 43 feet (13 meters) in circumference. Imperial Red Porphyry is one of the hardest marble stone ever. It came from the quarry of Mont Porphyritis (Egypt), the only source of Imperial Red Porphyry in the world. It was very hard and dense, extremely difficult to carve. Once the enormous stone was excavated, it would have had to be transported by oxcart along what was known as The Porphyry Road, right up to the Nile River, from where it was shipped to Rome in one piece – a total distance of around 1,000 km. The sculptor(s) needed great skill and very very hard tools to accomplish this work. We still don’t know to this day how they managed to manufacture such tools in the 1st century AD – we only rediscovered how to produce such hardened steel in the 19th century! It is a staggering feat of engineering and human ingenuity. And all this for a bathtub. Well, it was much more than a bathtub. It showed the rest of the world that only the Roman Empire could accomplish such an extraordinary feat. Such artefact projected a power and a prestige that only a Roman Emperor possessed in those days. Quite amazing, even to this day!

As I continued walking through gallery after interminable gallery, I started feeling nauseous by so much opulence and display. When I finally reached the exit door, I was near comatose. It wasn’t just the luxury, it was also the portrayal of so much gore, bestial behaviour, unmentionable brutality, as well as occasional ecstatic expressions. Reflecting on it all, reminds me of just how inherently violent the Christian religion was born out of. A violence that stayed with it throughout its history. Shaped out of violence and into violence. Not just at its beginnings, under Constantine, but all through Medieval times (the crusades), the Renaissance times (inquisitions, beatings and pyres), the Counter Reform, the Jesuit order, colonisation missions and so on. Mixing a middle eastern borne monolithic religion with a naturally passionate Latin temperament makes for naturally violent culture which leaves a deep mark in our collective unconscious.

The Romans

Wondering around Rome, even if only in my case for a couple of weeks, I came to wonder how the Romans succeeded so successfully at adapting themselves to such a dramatic, traumatic history, over so many centuries? Of course, I thought, Romans themselves were also the authors of that history, not merely its victim. I was very intrigued to note, in passing, that the city was sacked a record 6 times in its history (the last being in 1527 under Charles V). Probably a reflection of Rome’s notorious savage and systematic looting of foreign lands over the whole of its antique and not so antique history. That in turn probably inspired much resentment, desire for revenge and for stealing back I would think.

Of course, Rome is not the only city to have had such a traumatic past. The list is endless: Shanghai, Berlin, Baghdad, Moscow, Beirut, Hiroshima, Mexico City etc… However, I can’t think of any single major city, still standing after 23 centuries, which has experienced, more or less constantly, violent upheavals throughout and right up to the middle of the 20th century (with the fascist 20-year episode). And which is still standing proud on its two legs.

I kept wondering what it was that makes Romans so resilient over time.

Romans are deeply emotional people, unlike us northern Europeans, which tend to be more cerebral. Their natural mode of expression, whether verbal (accented with much gesture) or visual, is naturally prone to exaggeration, for emphasis. A plain statement of fact in Rome is meaningless unless charged with emotional colour. Here, people do not express themselves in shades of grey, rather in black or white. In peaceful times, I guess this shows as street cunning, dramatic expression, and straight talk. During more tense times, I would guess aggression and violence are never far from the surface.

I notice Romans don’t really seem to know how to laugh at themselves. I did not notice them for having much of a sense of humour. Sarcasm, wit and derision for sure, humour not really. As if everyone is just too important for self-deprecation. Here it is all about posturing, making sure you present yourself under the best light. People are out to impress, to show they are part of the tribe, not some outsider-come-foreigner in shorts. Proud and cocky is more like it.

Another thing I notice about Romans is their deep sense of family. Family seems always to come first, whether at home, in business, or in forming alliances. Family has always been, and remains, the strongest line of defence against any form of outside force. When I think of the mafia phenomena, a very Italian thing, to my mind it is an illustration of how strong the family, come tribal culture, is and remains to this day.

This unrelenting sense of family is synonymous with an equally deep attachment to tradition. Any attempt to change things, to alter the status quo, whatever the historical period referred to, will likely run into family resistance. I suspect that if Government (which, incidentally, though not coincidentally, always seems made up of impossible coalitions) wants to reform anything, it needs a general family consensus, as otherwise nothing will happen. Family and tradition are the ultimate force against any form of coercion or attack.

I notice how essentially visual Romans are. Unlike say the British, who seem to me much more auditory and don’t really care much about appearances (except if it is outrageous or calculated to be understated). Romans are second to none to come up with highly imaginative, deeply subjective images, to promote their beliefs and myths. Whether of a pagan or religious inspiration (not that dissimilar given the descent line from one to the other) this city is a dramatic illustration of that deep trait. It is often very physical. In many places (churches in particular), it is blood, gore, crucifixion, slaughter, carnage, life or death. In other, more contemporary places, you find wonderful frescoes on buildings facades, sometimes very amusing. Also in some squares you can enjoy deliberately contrasting old versus new settings that can be very eye-catching.

I also love the many graffiti’s, come street paintings you see everywhere.

I also very much like the way their modern museum display and contrast the old and the new.

Rome is the seat of elegance.

A particular illustration of this visual tendency is when you think about Roman women. Women have always played an important role in the city’s history. For a very long time in very much a subordinated role but fortunately, this seems at long last to be changing, as I notice today’s women are finally well on the way to occupying a full fledge role in society. But, coming back to their visual tendencies, two things stood out for me.

The first is that when I wondered amongst the elegant streets in the city centre, I could not help but notice that as much as 4/5 of boutiques are dedicated to women – dresses, shoes, handbags, jewellery, underwear and what not, all rivalling for women’s custom. And all very visual.

The other thing that has always struck me is the manifestations of the Roman male anima, which Jung says represents the feminine part of man’s psyche. This male anima has and continues to play an important role in the cultural landscape of this city. Roman mythology has always portrayed women in a complex, often contradictory manner. Ranging from the strong misogynous Catholic church image, where a woman is either a Madonna or a temptress, and not much in between. To the many feminine archetypes – the Venus symbol, the Spider Grandmother, the Cat, the Rose, the Moon, etc. Not to mention the anima as portrayed by its Italian film directors (Fellini, Antonioni, Sergio Leone, Pasolini etc.). I don’t think any other city projects its male anima in such a strong, complex, yet so distinctive a manner. As intangible as this sounds, its manifestations are very much tangible. And distinctly different from the other Latin countries such as France or Spain.

Back to the Romans. What about their politics? Throughout their turbulent history, I notice they seem to have been constantly obsessed with defining and arresting power. Well, its leaders at least. Maybe this is because, deep down, I think Romans dislike bowing to power, as they seem rather more naturally prone in defying it than accepting it. Throughout their history, leaders here seemed to have always worried not only about how to secure power, but also how then to keep it and make it unassailable. The script seems to be: if you have power, apply it ruthlessly, or else someone will rapidly challenge you for it. To my mind, it’s as if their deep underlying belief is that power cannot be shared but must be owned, in full. If you really need to share that power at first, by say forming a triumvirate to wrestle it away from an ultra-conservative Senate for example, always then ensure you simplify it down to its simplest expression of ONE, at the earliest opportunity. And watch out for the knives.

Related to this, I also notice the Romans’ obsession with boundaries. As I was guided through this wonderful city, I realised that Romans appear to have always been obsessed with boundaries. The boundaries of the city, of authority, of the Rubicon, the boundaries of intra-and extra muros, and so on. Why is that I wonder? Perhaps the reason is their natural inclination to constantly test those boundaries. So they exaggerate their importance by painting them, figuratively speaking, bright red. Which nobody falls for….

Bottom line ?

No question about it: Rome, unlike many other major capital cities, has really moved me. It is unique in the way it continues to exercise such a powerful draw.

That said, I walked away with mixed feelings.

On the one hand I sensed quite strongly the underlying sense of violence that, while hidden, is still so visible in all its buildings, its art, and its history. That somehow bothered me, made me feel uneasy. Even if I certainly did not feel it in people’s attitude or behaviour towards me during my visit, as for the most part they could not have been more forthcoming. But I noticed it was a reserved charm, detached, somewhat theatrical, more akin to something put on for the foreigners (mind you, there are so many of us roaming the city, I can hardly blame them). Still though, quite often I thought there was something fake about it.

On the other, I immediately fell for the lovely landscape, the wonderful, hedonistic charm and that apparent casual way of living of the Romans. Not to mention that lovely Mediterranean food, second to none. One of my big discoveries was those fried artichokes, which I had never had before. Must find the recipe.

Would I live in Rome? I don’t think so, despite the old charm of the setting. I think the Romans would drive me mad, with their theatrical emphasis. I am sure you can live very well there, meld into a cosmopolitan group of people, just picking the ripe fruits and not bothering much about the rest. But for how long though, before it rubs off?