As far as I can recall, I have been thinking about visiting Auschwitz pretty much all my adult life. Annie, who could not bear to look or read about war atrocities, had always refused to even contemplate the idea. Watching a documentary or film about such events distressed her. Not because she didn’t believe they happened. She believed it all right, having had an uncle who was deported to Auschwitz following a neighbour’s anonymous denunciation to the occupying German forces on trumped up charges. To her, all this was an ugly manifestation of the animal spirit that lies deep inside us, something she had a visceral reaction towards, beyond words.

As for me, I am not sure what I can ascribe my compulsion to. If I think more closely about it, I have always been perplexed by two intermingled phenomena which have both fascinated and subjugated me.

The first is to try and imagine how one can blindly subscribe to an implacable, lunatic ideology, leading to the most barbarian actions towards certain people, whilst, at the same time, being a well educated, rational human being, from a high cultured country. The gothic incarnation of a Jekyll and Hyde personality within an elite group of people who have fallen under an angry spell.

Secondly, and throughout my life, I have also had a profoundly visceral, uncontrollable antipathy, even hatred, whenever confronted with arrogant authoritarianism, abuse of power and bare faced malevolence.

While a student, I had read Victor Frankl’s “Man’s search for meaning”. That small book had made a profound impression on me. It still does. In it, he shows how a man can keep a rational mind to steer his will to survive, even while experiencing the most degrading and atrocious humiliations a system can inflict on a human being.

How one can keep one’s sanity while being reduced to a hairless body, with no other identity than that of a number tattooed on your arm, constantly fearing imminent death, hunger, bitter cold, painful physical discomfort and so on. Would I have been able to endure such torture, I half wittingly wondered ? I had also read Primo Levi’s “If this is man”. He too experienced Auschwitz. In his book, there is a scene which has stuck indelibly in my mind. Soon after his arrival by train, late one winter day, he was asked to strip naked, and then walk up to an officer in a barrack, who, after a cursorily look and with a simple movement of the hand, indicated he take the left door rather than the right one behind him. Of course, Levi had no idea where either door led too. Only later did he find out that the left door meant hard labour, while the right door meant going straight to the gas chambers.

I also saw many films and documentaries (Shoa for example). Had heard or participated in discussions when some people (too many) contended it was all an aberration of history, which today was unlikely to ever repeat itself. Really ? Events since, such as Cambodia, Serbia/Kosovo, Rwanda for example, are patent examples that make you wonder how anyone could believe the accidental historical aberration line. Human bestiality is never expunged from the human heart and mind. Man descends from the animal kingdom. We still carry primal instincts, even if they remain buried deep somewhere in our collective unconscious. Under certain conditions, these can be awakened, when, for example, our very survival is suddenly threatened.

All of this kept stirring up something in me, from I don’t know where, and compelled me, following Annie’s passing away, to finally go and see Auschwitz for myself.

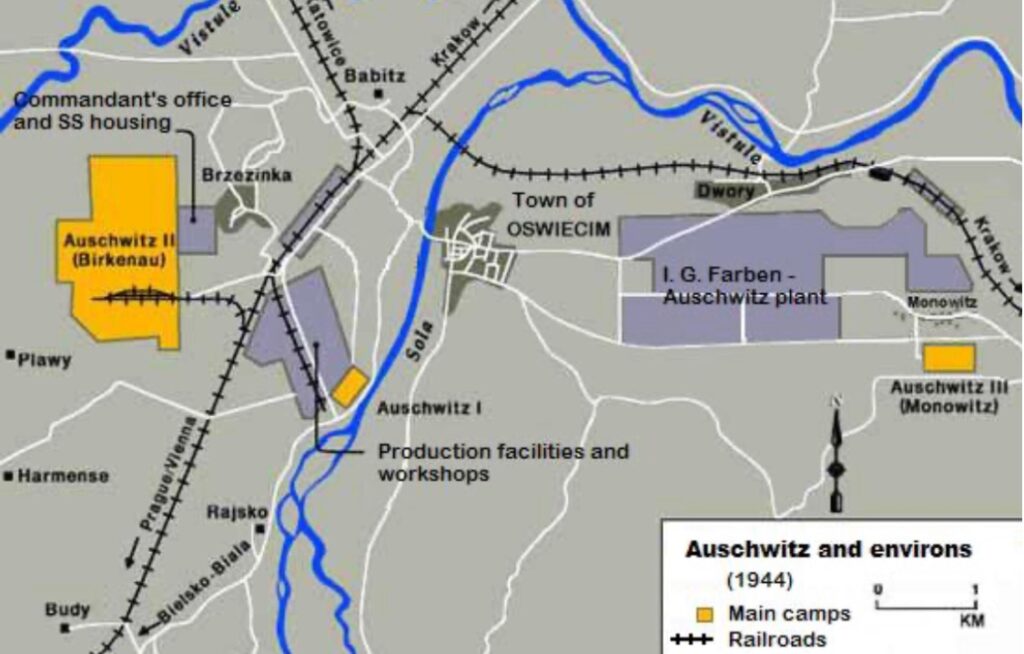

The actual Auschwitz complex lies about 65km (40miles) south of Krakow. It was originally occupied in 1940, around an old abandoned Polish army base. During the first year of its existence, the SS, and police, using forced labour, cleared a zone of approximately 40 km2 (15 square miles) as a “development zone”, reserved for the exclusive use of a new camp.

Today, when you arrive there by air conditioned bus, it feels like you are preparing yourself to visit a theme park of sorts. Big modern parking facilities, clear friendly signs towards the entrance of the complex, turnstiles, memorabilia shops, and coffee machines. You can’t see anything of the camp from the arrival area. Once through the large modern reception area, you must walk along a half-sunk concrete alleyway, with loudspeakers quietly giving out the names of some of the many victims killed there. Eventually you arrive at the famous “Arbeit macht frei” (Work sets you Free) old iron gate entrance, with its unmistakable wooden huts and swing barrier – the older entrance to Auschwitz I.

Auschwitz I was in fact the abandoned Polish army barracks facility. The Germans started out by using it as a place to lock up Polish and Russian prisoners of war. Very quickly though, the psychopathic brutality of many guards quickly showed up. Many of the prisoners were tortured, hanged or shoot in all impunity. The existing barracks housed around 15,000 prisoners, which later surged to 20,000. Within less then a year after their arrival, the SS started experimenting with Zyklon B gas in the basement of one of the barracks, to test its efficacy as a killing gas. As these tests were going on, at the same time in Berlin, the idea of a “Final Solution” to the Jewish question was being articulated. It eventually took form. A massive project of scaling the whole thing that was being experimented in Auschwitz, on a truly industrial scale. Let’s face it, when the industrious Germans set their mind to it, they are second to none to organise things in such a way as to meet the requirements of the set task, however momentous it may be.

The logistics were put in place to transport hundreds of thousands of people from all over Europe towards the camp (5 others were added elsewhere later). It was to become the largest part of the complex (35 times larger than Auschwitz I).

It had a dual purpose. It was an extermination camp for the hundreds of thousands that were deemed unsuitable for slave labour, and a concentration camp for those who could help the war machine to manufacture and build what the army needed.

First was the triage area, where they sorted out each incoming train load, carrying up to 2,500 people at a time (50 people per cattle wagon). Trains would arrive day and night, from all over Europe, go under the famous Birkenau train control tower, and stop along a very long earth platform. Men, women, and children were dismounted on this open air, long and large earth avenue.

They were asked to line up and then gradually move down the platform, right up to where a standing SS officer would quickly sort them out. At a glance, he would decide whether the person was strong enough for slaved labour (or experiments), and told to turn left, or deemed useless and shown to go right, straight for the gas chambers. Which of course they had no idea about. All this in good order, calm and with occasional music, as they stepped forward towards the gas chambers – which they were told were showers to get rid of the lice. Between 10 and 12,000 people would thus be killed daily, within one to two hours after arrival. The four crematoriums at the far end of the complex, all blown-up by the fleeing SS when the Russians arrived in 1945, could handle up to 20,000 bodies a day. Those selected for slave labour were taken to their barracks, sectioned for men and women. Auschwitz-Birkenau, while an industrial killing centre, was also a massive labour camp, that could house up to 90,000 people.

As for Auschwitz III, it was built later, nearby, for an IG Farben factory (the same major industrial company that produced the Zyklon B gas). Gradually, up to 50 smaller supplemental satellite facilities were added, all for specialised slave labour. The crass meaning of the “Arbeit macht frei”.

While in some of the surviving barracks in Auschwitz I show some harrowing displays (shoes, hairs, spectacles, suitcases etc), Auschwitz II leaves you aghast by its sheer scale and ruthless organisation. Just by looking at the layout plan, this was nothing else then an implacable, gigantic complex designed to select abled body by the tens of thousands to help German industry and the army machine to win the war while getting rid of the rest.

That rest, a group at least 10 times LARGER then the former, of all those who did not make the cut, were barbarically killed en masse and cremated as quickly as possible. The enormity of this massacre just defies the imagination.

It is estimated that the SS deported at least 1.3 million people to the Auschwitz camp complex between 1940 and 1945. Of these deportees, approximately 1.1 million people were murdered.

The day I visited the camp was a sunny august day. I shudder to think was it must have been like in winter. Many of the barracks have been raised to the ground but the layout and design are there to be seen. As I walked through the camp, I felt an eerie veil of sadness come down on me. No words can describe the horror of it all. Nothing can convey the suffering, brutality and remorseless bestiality that prevailed in that place. And to think there were another 5 other of these killing camps elsewhere in occupied Poland. The total number of victims were ‘officially’ numbered at 6 million, but who knows what the real number was. Much larger no doubt.

I needed to see and experience Auschwitz. I know I will never forget what it symbolises : our hidden primal bestiality, that lies dormant deep down our unconscious minds. Which, given the right circumstances, can be re-awakened.