In a metropolis of 34 million souls, Delhi unfolds like an endless story, each chapter more fascinating than the last. It’s a microcosm of India itself – a swirling mix of poverty and opulence, ancient traditions and modern ambitions, all set against the backdrop of its extraordinary cultural heritage. Yet Delhi stands apart in one striking way: here, women are carving out new freedoms that contrast sharply with much of the country’s deep-rooted gender inequality.

The city’s modern identity was forged in the crucible of the past 150 years, but its soul reaches back much further. Together with Agra, its sister city 220 kilometres to the south, Delhi was the jewel in the Mughal crown. These descendants of the Mongols swept into Northern India in the early 16th century, leaving an indelible mark that still colours the city’s character today.

The Mughals were more than just fearsome warriors – they were cultural alchemists. Their red sandstone fortresses and magnificent mosques were just the visible symbols of a deeper transformation. They brought with them a Turko-Mongol culture, influenced by Persian culture, that gradually merged with certain Hindu traditions, creating something entirely new.

They developed Urdu as court language (Persian-Sanskrit-Arabic mix), even if Hindu tainted Persian remained the official language. You can still taste it in the food, and see it in everything from formal gardens to the art of pigeon flying.

By the late 18th century, as the Mughal empire began to fade and the East India Company (EIC) tightened its grip, Delhi’s population of 200 million started to dwindle. Then came a twist of fate: on his first and only visit in 1911, King George V declared in Calcutta that Delhi would become British India’s new capital. The city’s fortunes reversed as the British Raj left its own strong architectural stamp on New Delhi. It too sought to project its power.

Then the 1947 Partition with Pakistan brought another seismic shift. As Muslims departed and Hindus and Sikhs flooded in from northern Punjab, Delhi’s population exploded by 90% in just a decade. The city’s culture was transformed yet again, a metamorphosis brilliantly captured in William Dalrymple’s “The City of Djinns“.

Seeking to peel back Delhi’s glossy tourist veneer, I found myself drawn to its raw edges – where old meets new, where survival means ingenuity, and where daily life plays out in all its unvarnished glory.

Beyond the Tourist Trail

My first discovery was the magnificent Gurudwara Bangla Sahib Sikh temple, where gold-covered inner sanctum walls tell only part of the story. To me, the real marvel lied in its massive kitchen, serving free hot vegetarian meals to anyone who walks through its doors – 10,000 meals daily, swelling to an astounding 100,000 on festival days.

Here, the mathematics of generosity is simple: 25-kilo bags of flour, vegetables and fruits arrive by tuk-tuk, donated by the faithful. Women, many volonteers, knead dough and roast chapatis in a choreographed dance of service that runs 24/7, 365 days a year. In a world of increasing isolation, this ancient practice of community feeding offers a powerful counterpoint to Western individualism.

An early morning rise

One morning, guided by a young doctoral student, I witnessed Delhi’s winter dawn by the Yamuna River. The infamous smog, drifting in from the burn-and-torch countryside fields, transformed the rising sun into a mere orange spectre, floating above waters that carry a sobering 350 million tons of raw sewage annually. As a young couple drifted by in a rowing boat, seeking the perfect wedding photo, the irony was stark – beauty and degradation coexisting in the same frame.

Nearby, a cow shelter offered another picture of contrasts. While sacred cows enjoyed shelter and regular meals, human beings slept rough across the dirt road. Along the walls, rows of cow dung patties dried in the sun, destined to become heating fuel – a reminder of how Delhi’s residents ingeniously repurpose everything.

At a car junction, dolled up eunuchs, once harem guards, hustle stopped drivers for money (yes ! drivers do sometimes stop at red lights). Apparently one of their main source of revenue is to bless newborns for a fee. Refuse to pay and the blessing turns into a curse. Hindus being superstitious, they eventually pay up.

In a nod to Mughal traditions, we visited a wrestling academy where promising young athletes train with minimal equipment but maximum determination. On a simple round mat in a makeshift shelter, future champions practice an ancient sport that might just be their ticket to a government job and some financial security.

Picture above right: to prevent men from pissing against the wall whenever nature calls, which they do everywhere, the owner decided to put picture ceramics of holy deities. It worked ! The wall is dry.

Kabootarbaazi (Pigeon Flying). This goes back to when Mughals used pigeons for messaging. Pigeon handlers today keenly practice their ancient art against the city’s modern skyline, by competing against each other. The birds take off from their roof tops, and the flock is brought back at will. They also hold annual race competitions as to who has the fastest pigeon. Wonderful sight.

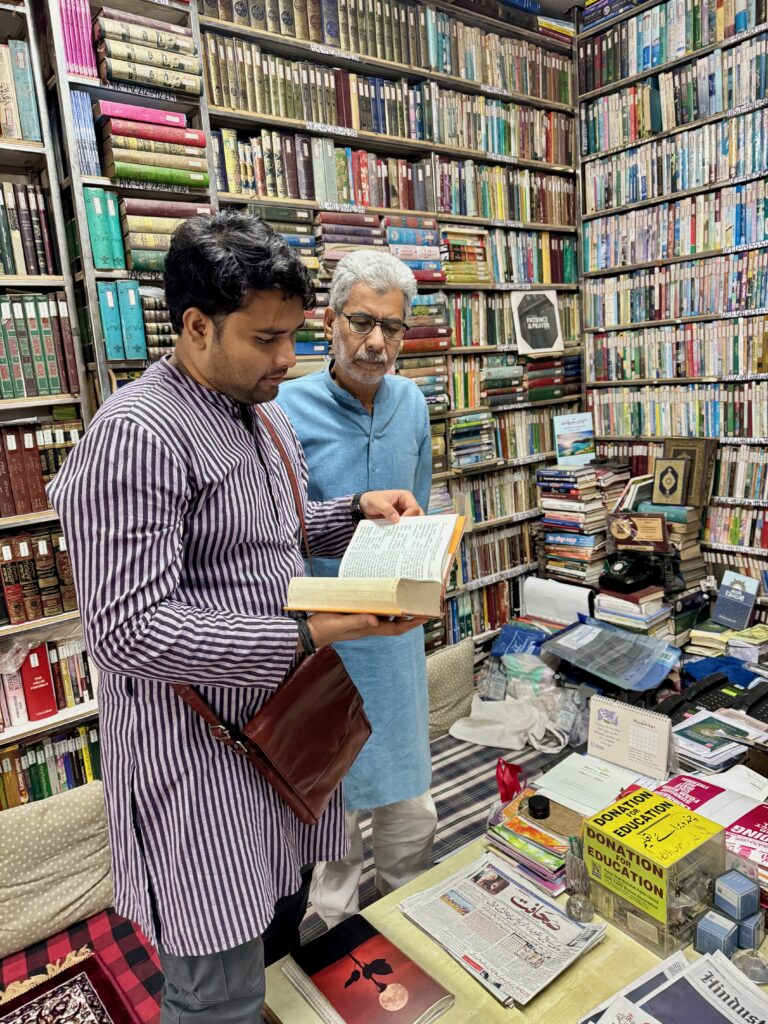

Another old but dying tradition: selling books in 12 different languages, starting with Urdu and many other dialects. This little bookseller was tucked away in the most innocuous little alley way that you just could not find unless you knew of its existence beforehand.

The bookseller was an erudite man, with wonderful courtly manners. My student guide was obviously a regular visitor.

Cloths are gathered in bundles from collecting charities, then ‘cleaned’ and cut in strips for recycling use. Delhi is a bottomless source for old discarded clothing.

Halal butchers operating in Muslim quarters only.

Slaughtering cows is illegal. Anyone found eating cow meat in a Hindu area runs the real risk of being lynched by a mob (happens several times a year !). I even heard that, very occasionally, the mob lynches accidentally wrongfully, not always able to tell the difference between mutton and beef …

Children of the Station

The story of Delhi’s street children unfolds daily at New Delhi Railway Station, where the city’s underbelly reveals itself through the eyes of Junaid, my guide from the Salaam Baalak Trust. Dozens arrive every day, runaways or lost children. A former street child himself, Junaid, about 25ish (he doesn’t know his real age), strips away my comfortable assumptions with frank directness. Every wrong answer I offer about survival on the streets (“They spend money on food, right?”) earns a knowing smile.

His own story tumbles out like a raw screenplay: a flood in Bihar near the Nepal border, the loss of his father and sister, and an eightyish-year-old boy’s desperate journey atop a train to Delhi. The station, with its daily tide of 700,000 people, became both home and hunting ground for about 4 years. He learned the harsh geography of survival – which territories belonged to which gangs (a lesson learned through a stomach knife stab), where to sleep safely (on the vast station roof), and how to navigate the dangerous streets.

But Junaid’s story, harrowing as it is, pales against the perils faced by girls on these same streets. The nearby G.B. Road, with its hundreds of multi-story brothels housing over 2,000 sex workers, stands as a grim reminder of the dangers that lurk in the shadows. For young girls, every day is a gauntlet run past those who would profit from early child marriages, inter-caste unions, or plain rape.

Through Junaid’s eyes, the station reveals its secrets: children sleeping on latrine roofs, clothes drying on railings like flags of poverty. Money, when it comes, goes not to food (the temples provide that) but to glue sniffing and Bollywood movies – chemical escape and cultural education rolled into one.

In one of the Trust’s centres, I meet children aged three to twelve. Their resilience is startling – past traumas hidden behind bright eyes focused firmly on tomorrow. It’s a sobering reminder of childhood’s extraordinary capacity for resilience. A moving experience, believe me.

A Temple for Modern Times

On another day, the Swaminarayan Akshardham temple complex presents a jarring contrast – a Hindu Disneyland of staggering proportions. Built in just five years on 100 acres, it showcases both immense wealth and extraordinary craftsmanship. Seven thousand artisans carved 20,000 statues from pink Rajasthan sandstone, including 148 life-sized elephants. The temple, built without ferrous metal in keeping with tradition, boasts nine intricately carved ceilings and an inner sanctum adorned with semi-precious gems.

It’s overwhelming, impressive, and perhaps a touch too kitschy – a monument to modern India’s economic muscle as much as its spiritual heritage.

The Sacred at Home

For many Delhiites, faith finds its truest expression not in grand temples but in humble home shrines. These personal sacred spaces – sometimes just a wall niche, sometimes a courtyard altar – reflect a practical adaptation to centuries of religious upheavals. When invading armies destroyed temples, the people simply brought their gods indoors. Today, local shops stock everything needed for these domestic sanctuaries, proving that in Delhi, as always, faith finds a way to survive and thrive.

This is Delhi – a city where every corner tells a story, where past and present dance an eternal one, and where the sacred and profane coexist in surprising harmony. It’s a place that defies easy categorisation, demanding instead that we embrace its contradictions and celebrate its complexity.