I started my trip to Northern India by visiting the province of Rajasthan. It is the largest Indian region, which covers just over 10% of the country.

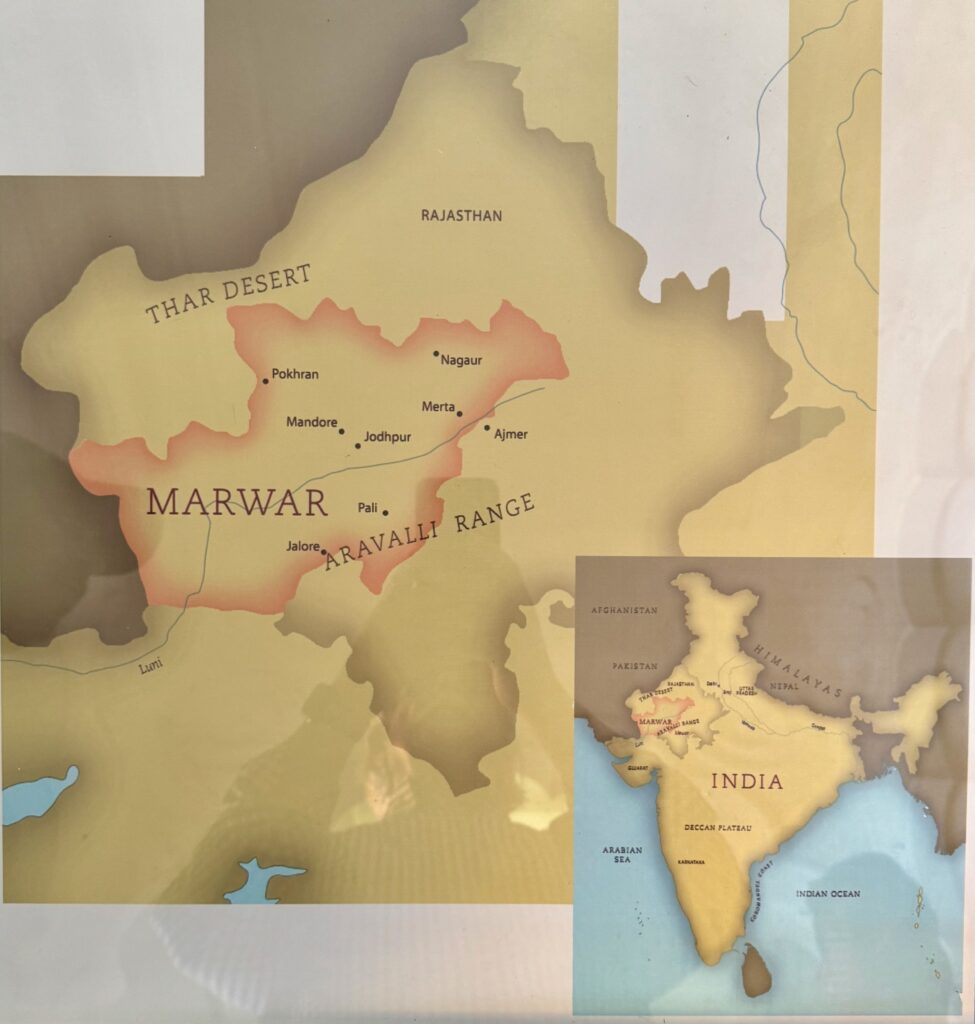

In the North West of Rajasthan lies the Thar Desert, where India conducted its initial underground atomic essays in the 1970s, under Indira Ghandi. In the South East lie the Aravalli mountain range, which cut across diagonally, one of the oldest ranges in the world. It is renowned for its granite deposits as well as it semi-precious gemstones.

In between those two areas is a large semi deserted region, cheerily known as the Marwar (the Land of Death). A harsh area, with little water. Through it ran the vital trade routes that linked the fertile Indus valley and the ports of Gujarat in the West, to the valley of the Ganges in the East and the fertile South. Since early centuries BCE, right through Medieval times, and up to the middle of the 20th century, camel caravanners passed through Rajasthan and its famous trading posts.

Places such as Mandawa, Jaisalmer, Bikaner, Jaipur and Jodhpur, all different in appearance, were all built around the same model. Namely a protective and massive fortress atop a rock or earth mound, that housed the local Rajput’s (son of kings), which overlooked the bustling trade town beneath and around it. It is there that the wealthy and prosperous merchants lived. And to show off their wealth and status, they built their fabulous havelis, that Marwar is famous for.

The word “haveli” comes from the Arabic word hawali, which means “partition” or “private space”.

Havelis are beautiful, multi-storeyed, manor houses, built in accordance with indigenous Hindu architecture style. They focus on defensive features, using local materials, and relied on local artisanal skills developed over generations. Generally these havelis have massive walls with defensive battlements, often with overhanging enclosed balconies. The layout inside can be complex, but generally they have two internal courtyards. The first one is for receiving guests and conducting business, while the second, most inward, courtyard is for family housing and very much the domain of women.

The outer walls of the havelis, have elaborate windows and elevated doors, to help condition indoor temperatures.

Mandawa

My first stop was in Mandawa, which today is a sleepy village of around 2,000 people. As elsewhere in Marwar, the climate here is hot in the summer (up to 40c+) and chilly in the winter nights. Water is a scarce resource.

As the trading post grew into a successful trading town, it got its protective fortress in the 17th century. Surrounding the fort, the havelis have three distinctive features.

First they have a thick outer wall, built with a mixture of clay and lime, filled with air bubbles. This helps keep the inner layer more or less at constant temperature, thanks to the captured air bubbles. The external facades are covered with a fine grounded white material, a mixture of lime and marble, which was carefully plastered and ground in with seashell powder, so that it would reflect back 70% of the direct sunlight.

The second feature is an astute air conditioning system of sorts. The upper part of these walls were fitted with many small latticed windows and suspended wooden doors. Depending on which way the day’s breeze would be blowing, a cool air flow could be created by opening the windows and suspended doors of the facing facade. The fresh air would then flow through inside the haveli, through the rooms and into the inner open air courtyards, thus creating an internal air current which is drawn upwards by the warmer air of the open sky.

Last but not least, the upper part of the outer walls, very soft to the touch, were covered with delightful frescoes. Representing carefully painted scenes, that would depict daily life, folk mythology, religious stories, and more recent events (ex an airplane, a squad of uniformed British soldiers etc.). Many of these frescoes are still looking good after 200-400 years. The reason being that the artisans only used mineral and plant based paints, which they applied in multiple layers, each one having been carefully sanded down with the same seashell dust before the next layer was added on. Such work could be replicated today using chemically based paints, simply because they contain plastics. Plastic will eventually bubble up under the searing heat.

Bikaner

Continuing westward, I visited Bikaner, which also has a splendid fortress called the Junagarth Fort, built in the late 16th century. A impressive edifice, also atop a rock formation, containing a surprising number of both public and private rooms, still in surprising condition and displaying amazing wealth as well as ingenuity. The blue room shown below is meant to replicate stormy clouds, and had continuous water falling to cool the room. Really quite sophisticated.

Jaisalmer

Further west lies Jaisalmer, not far from the present Pakistan border. There the whole old town and its fortress are atop an elevated mound, making the ensemble look like a medieval fortified city. Everything is built with interlocking sandstone of a lovely beige colour. It has massive ramparts, inside of which are the palace, the havelis and a remarkable Jain temple, with wonderfully carved sandstone. Whether up in the old town, or down at the foot of it, lie a network of courtyards and halls featuring stone-lattice work, so finely carved, that it often looks more like sandalwood than sandstone.

Jodpur

From there I swung southeast, towards the large city of Jodpur (1.2 m people), nicknamed the Indigo city. Here again dominated by the mighty Mehrangarth Fort, high up on a massive, dominating rock mound.

All of these impressive places, with their fortresses and havelis, suddenly saw their old prosperity dry up some 80 years ago, in 1947 with the independence of India. And the partition with Pakistan, which simply cutoff the trading routes. The massive forts with their beautiful havelis were often abandoned, put under lock and key, with their owners making off for the larger cities to reinvent their businesses. Today, many Marwari families have transformed their traditional trading businesses into industrial complexes. Tourism has become a major economic driver, with heritage hotels of high standards offering their wares, as well as handicrafts emerging as a new trading commodity.

Many of these towns are today in survival mode, often in poor state, sometimes even looking decrepit and ghostly. As is the case with so many places in India and in the world at large, these edifices stand as witnesses to a fastuous times that are no more. The heart beat stopped for one reason or another, leaving behind many impressive edifices that just decay away, unless some UNESCO type organisation recognises their architectural, religious or cultural significance to human history and come to the rescue. A constant reminder that any human endeavour, whatever its size, always has a beginning, a middle and an end.

Makes you wonder what our mighty modern metropolises might look like in, say, a century ?