Have you ever wondered how deeply our cultural roots shape our thinking, even after we try to detach ourselves away from them? As I travel through India, this question has taken on new meaning for me.

I’ve long been puzzled by how Western science grapples with certain concepts. Take quantum physics, for instance – after a century, we still struggle with wave-particle duality and probabilistic reality. Or consider why we continue to teach Euclidean geometry when now living in Einstein’s curved spacetime.

As I pursue my solitary travels across India, things are shifting. Among its bustling millions and ancient wisdom, I have just stumbled upon a story that crystallised around the story of Brahmagupta, the 7th-century mathematician from Rajasthan.

Brahmagupta wrote two works – one theoretical (“The Opening of the Universe“) and one practical (charmingly titled “Edible Bite“). I love that title, as I have always been on the lookout for ‘edible’’ bites when dealing with abstract notions. Particularly in maths and physics, subjects I have never been very good at, but have always remained fascinated by.

His revolutionary insight? Seeing zero not just as a placeholder, but as a concept unto itself.

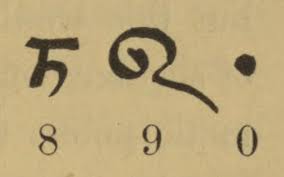

The history is fascinating: Hindu mathematicians developed our familiar numerals (1-9) around 300 BCE. Zero began as a humble dot on a stone inscription. It then evolved into a yawning circle, serving to separate orders of numbers (tens, hundreds, thousands). In the ensuing 900 years, Hindu traders adopted the decimal system that their mathematicians had come up with, by using the zero as a placeholder.

This is when Brahmagupta arrived in the 7th century CE … He recognised zero as representing ’emptiness’ – not nothingness, but emptiness with infinite potential. His insight was to realise that below zero lied the opposite of positive, i.e. the negative. And it is this insight which opened the door to negative numbers and to the whole realm of algebra.

But here’s what struck me: Western civilisation took another 800 years to fully embrace these concepts. Why? Because our Christian worldview sees creation as starting from nothing, until it was created by an act of God. For us, before the divine creation, there was nothing. As a consequence we could only think in the positive: something either exists or it does not. Period. For Christians, the universe has a beginning and an end. It is linear, not cyclical. This made it hard to conceive of ’emptiness’ as something meaningful. In contrast, Hindu-Buddhist’s thinking comfortably embraces emptiness as a generative force.

It is now that I realise we Europeans only came across the nine numerals and the conceptual 0 in the 12th century. When a certain Ludovico Fibonacci of Pisa, who was conversant in Arabic, learned about the Bramagupta’s concept from the invading Arabs that occupied North Africa and Spain. Those same Arabs who had in turn learned it from the Hindu-Buddhists when they had invaded northern India in the earlier 9th century.

This realisation was a “aha” moment: my Western cultural inheritance had been invisibly warping my understanding of this all along. Even as a non-believer, I inherited its theological framework.

The implications of Bramagupta’s zero concept are staggering. Without it, we wouldn’t have:

- Algebra and negative numbers

- Modern double entry accounting and finance

- Coordinate geometry

- Calculus

Which just makes me wonder: what other cultural blind spots do I/we have ? Many of course, until we start travelling and somehow gain new perspectives that help us see beyond our inherited worldview.